The collected edition of the Godmother Part I – III is now available at Amazon in softcover at this link.

Jason A. Archinaco

The collected edition of the Godmother Part I – III is now available at Amazon in softcover at this link.

December 11, 2020

“The Last Testament of The Godmother” (as told on her deathbed) – Part I is available on Amazon at this link. This is a work of fiction.

My short story “The Diner: Tales from Voxhalla Issue 1” has been published by Retro Ronin and can be purchased on Amazon at this link. Enjoy. I am hard at work on another. – JAA

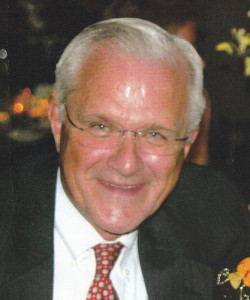

My father didn’t respect a lot of attorneys because he believed that, as a lot, they were rotten. But there were a few he did. One of those guys was Daniel P. Stefko – “Dan.”

My father and Dan met working on a tricky construction delay case based in Atlantic City around the time I entered law school. I was in Hilton Head with my father when I met Dan. And by met, my introduction came in the way of a brief that Dan had co-authored on the construction delay case.

“Jay, do you want to know my test for an attorney?” My father said as he handed me the brief. Whether I wanted the answer or not, I was going to get it.

“Would I want this guy defending me if my life was on the line?” He stated that not as a question, but as an assertion. “Dan is one of the guys that passes that test, and very, very few do. You should send him a resume and return to Pittsburgh to work with Dan if he will have you. Because if you want to be one of the guys that passes my test, you need to learn from someone that already does.” My father saved the most important part for last, as he usually did.

“Oh yeah, and he is honest too, something that seems rare in the legal business. So he proves you can be honest in the profession and still be one of the greats.”

Before my interview with Dan, my father had told me about his icy eyes, booming voice and imposing presence (as if I didn’t already have enough to be nervous about). I had already imagined him a modern day Clarence Darrow, or perhaps a notoriously tough Socratic interrogator like Boston University’s Professor Rickman.

Of course I was sweating when I first met Dan. And then he looked at me with those icy blue eyes – ones that transfixed people into telling the truth – I stood there motionless, not even extending my hand to shake his. It was then that he shook my hand and pulled me in for his patented “long-lost uncle half hug.” Everyone that Dan cared about knew that handshake – because it was the first way that he made you know he cared about you – and that he would look out for you. It all started with those eyes – and that handshake. That handshake just sucked you in, and as he hugged you, you realized how solid a man he was – a man who regularly exercised in private, and who resultantly looked a lot younger than he really was.

I did a lot of work for Dan over the years, grinding away at the trade, learning as much as I possibly could from him. Even with people helping him (me included), Dan was one of the partners that I routinely saw in the library. He liked to do his own research because he said it kept him sharp. Dan was one of the guys setting the standards for the young attorneys, proving that no matter how many books identified someone as one of the “best attorneys,” titles didn’t win cases, hard work did.

As general counsel of our firm he also led with his ethics. He promoted equality in the workplace, especially for all minorities, including gays and lesbians long before that was the politically correct thing to do. Dan also set the standard that everyone was required to tell the truth. What Dan preached made sense to me because those were the same things my own father had taught me – so I listened (even if he didn’t always think I did).

Dan believed that the law was a noble profession. Those that listened to him learned that there were no exceptions to telling the truth. If you needed to lie to win, then you surrendered instead. Dan was the kind of guy that handed over the bad documents, and then settled the case. That was Dan’s integrity, always doing right by the client because, in the long run, he believed that telling the truth was always better than covering things up.

After I left the defense practice for predominantly plaintiff work, Dan and I had a number of cases against each other. Ultimately, one of those cases turned into an incredibly tense affair where it felt like everyone had nukes pointed at each other. Despite that level of intensity, Dan and I had been able to work on the case together professionally.

Even so, when my partner Bob and I headed to the courthouse for a settlement conference on the case, it felt a lot more like we were attending a nuclear summit with Dan as the opposing negotiator. Despite his client’s hostility towards us, Dan still greeted me with his signature handshake – pulling me in close, and reminding me of how I felt about him – one of my mentors. I have had a few fathers in the practice of law – and he was certainly one of them.

That day, in private, we duked it out before the Judge, jabbing each other about the strengths and weaknesses of our respective cases. Nothing went in the right direction, and when we left the Judge’s chambers, we were all a bit heated. The case hadn’t settled, with tensions running high.

As I said goodbye to Dan, he asked that I speak with him privately. Despite both of us being in obviously agitated moods (I liked to joke to Dan that I inherited he and another of my mentor’s tempers), we agreed to speak.

It was when Dan asked me to sit next to him on a courtroom bench that I realized what he was about to deliver very bad news. Bob and I had both noted Dan looked pale – but it wasn’t until then that I realized what that meant. And, there, Dan told me had leukemia. Although we both knew what that meant, Dan told me he was going to fight it – and he was going to beat it. And, he added, he was going to keep working. I had heard my own father say the same things to me before pancreatic cancer got him.

Dan kept working and fighting it – and darn well for a long time, I would add. He was fully ready to try that case he had against me. He only asked that if he tired during the trial that I agree to shorter days. “I am getting old,” he joked. We had a nice laugh about that.

And just when I didn’t think that the case could get any more intense, it did – when something unbelievably dishonest occurred. Not much longer I found myself calling Dan in heated anger, wondering if he knew what had occurred and demanding answers. It was at that precise moment that everything could have blown up in everyone’s faces causing massive damage. But the strength of Dan’s integrity prevented that from happening. I respected him, trusted him and followed the advice he gave that day, because he made it clear that he was dealing with the same thing I was dealing with and he didn’t want to see me get hurt.

“I am proud of you,” he said. “But this is a fight for another day, and you need to trust me on that.”

After our near nuclear meltdown, Dan and I continued to have cases together, which gave me an excuse to call him and speak to him about all sorts of things. Although Dan and I hadn’t always seen eye to eye (perhaps he had “trained me too well,” I said which elicited a laugh), we had talked through our differences. And, even though we were adversaries on cases, he continued to give me a lot of good advice along the way – including above all else to just tell the truth.

Dan continued to work, literally, until the day he died – with files at his bedside. Why? I asked him during one of our calls.

“I love the law,” he said. “And I will die doing it, but don’t worry, I don’t plan on dying any time soon.” He was upbeat and said that shortly before he entered the hospital to undergo his final treatments, ones that he didn’t survive.

Almost three years to the day that my father died, on February 11, 2014, Dan Stefko lost his battle with leukemia – and joined my father. The law, our shared jealous mistress, had me clear across the country when it happened.

Dan was a devout man of faith survived by a very large family. Included are his wife, children and grandchildren (of which there are many), as well as his extended family through the law – me included. It is through all of us that his legacy continues. Dan’s official obituary can be found here. Thank you Dan.

Thirty years ago today, on April 1, 1985 – that was the headline: “Villanova Wins the NCAA Championship!” It was such an impossible victory that when I called my father to tell him, he thought it was all an April Fool’s joke.

“If you had told me they lost by less than 10, you may have had me,” he said as he laughed into the phone.

My father had graduated from Villanova in 1965 and nobody more than him wanted Villanova to win that game against the invincible Patrick Ewing led Georgetown Hoyas. But, it was impossible, as everyone agreed, including the greatest handicappers in the world. The only way Villanova could win was if a miracle occurred.

My father was located in Paris at the time, running PPG’s European glass division. As a result of time zone issues and the added fact that my father didn’t want to watch Villanova get “blown out” – he never watched the game live.

Instead, I broke the good news to my father, who was 100% certain that I was pulling another April Fool’s gag (as I had gotten him before).

“Oh yeah,” my father asked. “What did Villanova shoot from the floor?”

“Over 78%,” I said calculating from a box score I had kept. My father let out a howl.

“They won, and they shot over 78% from the field?” He kept laughing. The detail hadn’t helped, but only had made the victory seem less plausible. It even sounded implausible to me when I listened to him say it. “Well, I have to hand it to you,” my father said. “Great April Fool’s joke, down to the detail of them shooting over 78% from the field. And the thing is, Jay, I know it’s all a joke – but Villanova really would have to shoot like that from the field to win – and that’s not plausible. I would love to believe you.”

So, I provided him with more details – down to the frantic ending where all Villanova had to do was inbound the ball to secure a 2 point win – and how Grandma had let out a nervous yelp as they did. I even told him that I was going to mail him the VHS tape recording I had made of the game and that he could watch it himself. But, he still refused to believe that Villanova had won the game.

He still didn’t believe it by the time he reached a newsstand to buy a paper either. And, when he reached his local newsstand and read the French equivalent of “Villanova Wins the NCAA Championship!” he was certain that he must be reading the headline wrong, because while he could speak French relatively well, he had a very difficult time reading it. I had to have made it up, and he had to be reading it wrong.

He later told me that even when he confirmed that the headline really did say Villanova had won, for the briefest of moments he wondered how I had planted the newspaper. We had a good laugh over that.

“It really was a miracle Jay,” he said years later. “And I just couldn’t believe it.”

On April 1, 1985, the Villanova Wildcats implausibly defeated the invincible Georgetown Hoyas. The documentary Perfect Upset: The 1985 Villanova vs. Georgetown NCAA Championship chronicles the team – and the little man who inspired that team – Jake Nevin, Villanova’s beloved trainer who was dying from ALS during that championship run.

Although the team had underachieved all year, everyone knew that team was going to be the last Villanova team that Jake was ever going to see play the game he loved. He knew it, and they knew it. It was Jake’s last and only chance to win a national championship – and to go out the ultimate winner. And, at the end of the day, there was no way that those players were ever going to let that beloved, dying little man down – or their excitable Italian coach Rollie Massimino, who my father referred to as “the guy who made good sauce.”

When my father was dying, we watched Perfect Upset together, to relive that game – and the fantastic April Fool’s joke I never played. His vision impaired from one of the strokes he had, he couldn’t make out anything other than moving shapes.

“It’s ok,” he said to me. “My hearing is just fine, and I remember the whole thing like it was yesterday. That was the greatest basketball game ever played. And, that was the greatest April Fool’s joke you never played.”

And for anyone who only read the headline to this story and, for the briefest of moments thought Villanova just won the National Championship, Happy April Fool’s Day!

My father loved boxing as much as me; it was one of our shared vices. Over the years, we watched a lot of fights – none more exciting than Mike Tyson. Yet, in the twilight of his life, my father decided to tell me that his favorite fights were the ones I staged and simulated through an Avalon Hill Board Game named Titlebout – (he couldn’t remember the name and called it “that game with the little yellow cards and the bios on the back.”). Titlebout was created by two Pittsburgh brothers named Jim and Tom Trunzo, lifelong boxing historians and fans. And it remains the gold standard in boxing simulators, producing historically accurate results.

Before computers came along, the simulations were all by hand – flipping cards and checking numbers. So fighters in my simulated world fought less than they do in real life – and a top fighter in my universe of boxers would maybe fight twenty five times before they retired. I didn’t bother with time periods, so a slew of champions were mixed together – guys like Jack Dempsey, Muhammad Ali, Sonny Liston and Rocky Marciano – populated the ranks – along with Sam Langford, a man whose name is largely unknown outside boxing historians because racism kept him from a shot at the title.

In order to run the win loss records up though guys couldn’t regularly be fighting the likes of Langford or Liston, there needed to be “powder puff” bouts – guys with glass jaws – or guys that were good, but not good enough – that would always fail in the end. The goal I set out was for Muhammad Ali and Rocky Marciano to meet undefeated, so all the bouts were building towards that climax.

My belief was that Muhammad Ali was statistically the greatest boxer of all time, and was first at getting into his opponent’s head, with a close second to Tyson and third to Dempsey. No one could touch Ali overall (despite my respect for the talents of sluggers like Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano and Mike Tyson). And so I thought it was a foregone conclusion that he would be undefeated when he faced Marciano, because no matter how tough the opponent, Ali’s style was always dominant, particularly against sluggers. The only guy that could match him on style was Jack Johnson, but I had Ali ducking that bout before he faced Marciano – just like both Ali and Marciano ducked Langford, a tough match up for either of them. I wasn’t leaving anything to chance for the Ali versus Marciano undefeated show down.

As I mentioned before, in the mix of all of this were the so called “powder puffs” – the walkovers on the way to the big fight my father and I both wanted to see – Ali and Marciano.

My father loved Rocky Marciano, who was an Italian hero. He liked to laugh at how Marciano hid money in his toilet, and in curtain rods. “All Italians were like that back then, hiding money in the craziest places,” he said. “We were all afraid we were going to get robbed.” It made him laugh that even the heavy weight champion had that fear, and it made him relatable. “Marciano proved you could beat the odds,” my father liked to say. “And I wanted to believe that for myself.”

As for the fight itself, he said: “Ali was probably the greatest and had the style edge, but Marciano’s heart gave him a chance to win. He could never be counted out.” So my father chose not to predict the outcome. “You know who I want to win,” he said. “So no cheating. Or it will ruin it.”

So with no do-overs (or cheating as my father called it (they are now called save files)), along the way to that fight Marciano and Ali were both going to have to face perennial “powder puff” Primo Carnera. The description on the back of his Titlebout fighter card read as follows: “Da Preem was the biggest heavyweight champion ever! He was over 6’ 5” and weighed 260 lbs. He was also a fine person and courageous fighter. He only had one drawback. He couldn’t fight! Carnera’s climb to the top was littered with dives and set-ups (unknown to Primo). The gangsters that ran Carnera used him and discarded him when he no longer had value. In spite of all this, Carnera never gave anything than his best in the right and could take punishment downstairs. However, a hard shot to the chin and down he’d go. It was unfortunate that a good man like Carnera got mixed up with such unscrupulous men.”

Knowing that background as told to him by Grandpa, my father made Carnera a must fight for Ali and Marciano. If I was the play-by-play commentator, my father was the color guy – helping to flesh out my imaginary world by telling me everything he could remember about the boxers and what Grandpa had told him – and always adding the seedy corruption and drama that has been inherent in the sport of boxing. Imaginary gangsters made the fights more interesting.

Carnera had statistically virtually zero chance of beating Ali or Marciano, especially since the game didn’t have any “fixed” fight settings. With all his flaws, however, there was one thing on his Titlebout card that gave him a shot, his punching power. While not great, it was respectable, a seven on a scale to ten. In real life, he had 66 Kos in 84 bouts. And while I had given him no chance of landing a blow like Ali had on Liston, in the first round I pulled a series of cards from the playing deck that simulated exactly that. Ali was not only knocked down, but out cold. I stared at the game board, a hard cardboard playing surface with a 3d ring.

It was just an incredible turn of events that left me perplexed and questioning the integrity of the game. I wanted to cry, but didn’t. Instead, I went through the scenario again, over and over, flipping the cards, making sure I had not flipped them incorrectly. I had flipped them correctly. Other than the game being inherently broken, I could not find the answer.

So I asked my father to explain it, if he could. I wanted to still believe in the game, to simulate that big Ali versus Marciano fight. But the Carnera / Ali result had me questioning my faith in the game. What he told me was that in real life, Ali could never have lost to Carnera – unless the fight was fixed.

I reminded him that Ali got knocked out, and in the first round. It was the type of knockout some fighter’s egos never recover from.

“That’s because,” my father said as cool as could be. “Carnera’s gloves were loaded with lead.” He explained that Carnera’s hitting power reflected all the dives and fixed fights, and so the hitting power statistic on his card was inflated. In reality, the 66 ko wins in 84 fights were a sham with many the result of dives. “Grandpa said he hit like he had pillow cases on his hands,” he said. So, the card was in error, Carnera hit with less power than his card said. So, he explained, if the result with less power was different, then the result could be chalked up to the fix being in – and Carnera’s gloves being loaded with lead.

If I wanted, he explained, I could go back and redo the fight, this time with Carnera’s hitting power a 6, not a 7. That small change, he said, would make a huge difference – and “eliminate” the fix.

So I went back to the card deck that I had intact, and replayed this time with a 6 hitting power. Instead of the knockout, the fight had continued – and Ali had won easily.

Even though I could have erased that loss, I decided against it (although I have erased many loses to the ai over the years in videogames). I chose to continue in that imperfect world, the one where Ali lost. After all, he did lose – and the card did say Carnera’s hitting power was a seven.

I constructed a fiction that Carnera was an innocent bystander in the whole thing, to make my world consistent with his card. After all, he was described as a good guy who had just gotten mixed up with some gangsters.

Years later, my father, brother and I watched the real life equivalent of my Carnera / Ali Titlebout fight, when Antonio Margacheeto ran his mouth off before the fight against an undefeated Miguel Cotto so much that it was a certainty that Cotto was going to shut it for him. But the result turned out differently, with Cotto taking a beating before succumbing in the late rounds.

It later was discovered through investigation that Margacheeto had loaded his gloves. Cotto confronted him with the evidence that everyone saw, and he still denied it. But, in the end, the evidence was there. And ultimately there would be a rematch.

My father never lived to see the rematch of that fight. If he had, he would have said that was the best revenge a fighter ever got on an opponent that had cheated to beat him. I watched that fight with my brother, who I love. It was the greatest fight I ever saw, and he would agree. He would also agree that the Cotto versus Torres fight we saw live ranks second – (the greatest mini Rocky fight of all time, so great that it almost seemed scripted). And, as a footnote in history, my brother’s statistical ingenuity landed us tickets on the camera side – so we can be seen throughout the entire bout.

And as for Ali and Carnera, I told my father I decided to stick with the original result, fix or no fix, it was a loss. But, Ali would come back better the second time – that all the stars would be in attendance, even his favorite, Frank Sinatra. And Ali would make sure he took no chances, no matter how long it would take.

When that fight did happen, it was the virtual equivalent of the real life Cotto versus Margacheeto rematch, a brutal display that sent a message to the imaginary gangsters who had backed Carnera – that if they ever tried to affect the results of another bout in his career again, they would be the ones on the receiving end of the punishment.

Ali’s dismantling of Carnera was less about Carnera, a man oblivious to his own limitations (relying on my constructed fiction that he did not know the gloves were loaded), than it was about the gangsters that backed him. I described those three round blow by blow to my father from the notebook that I kept tracking the action, and how Carnera couldn’t answer the bell for the fourth round. Ali was triumphant in the end, his pride restored – and the villains defeated.

And, as for Ali versus Marciano, that’s best saved for another day.

Thanks old man.

-11/28/14

Whenever I was dogging it in football practice, I would turn and there would be Tommy Knox, staring right back at me. Tommy had this uncanny ability to know precisely when you were taking a play off. Without fail, the moment I did, Tommy was watching.

“What are you doing?” he would say as he grabbed your face mask and yanked. “Practice hard!”

Guys like that make football teams better. They were winners, always leaving everything they had on the field- and ensuring that everyone around did the same. If you didn’t elevate your play, then you had no place on the team. Tommy’s standard was uncompromising. Always play hard. Always play to win. He led by example, a phrase too commonly used today. But for Tommy, it was true.

My first appearance on the varsity team was on special teams – covering a kickoff. It was my big moment. And while I was just a Yoeman Johnson on the kick cover team, the moment wasn’t lost on Tommy.

A Junior – and not yet a Captain (but obviously going to be one as a Senior (he was)), Tommy was in my face getting me revved up for my big debut. By the time Tommy was done with me, between his facemask grabbing, yelling and pump routine, in my mind I was a mini Lawrence Taylor. I wasn’t just going to make the tackle. I was going to make the tackle, cause a fumble, pick it up and rumble for a touchdown.

“I am going to watch you,” Tommy announced. Who cared about the coaches, Tommy was the guy you wanted to watch you make the play. Once he saw what I did, I would be a legend.

The moment the ball was kicked, I sprinted towards it. The ball had traveled to the deep left side of the field. I was on the right side of the field. The man that was assigned to mark me was a distant memory – irrelevant to my mission. No one was going to stop me. I ran with reckless abandon, my only thought of making the big play in front of Tommy – being the hero.

I approached the first line of blockers, and sprinted to the left. No one was going to stop me.

The next thing I remember was looking up at Tommy who was standing over me as I came to.

“That was awesome,” he said, lending me a hand to pick me up, my back and helmet planted in the mud. Tommy began laughing once he saw I was ok.

“What happened?” I asked.

“You got knocked out,” Tommy said. “It was awesome. I will never forget that play. I hope you always play that hard.” He smacked me on the side of the helmet as he continued to laugh, and as he ran out onto the field to play defense. “Now watch me.”

I watched him the rest of the game and by its end I had figured out a few things:

1. The first blocker that I had come across had lowered his helmet and caught me clear in the chin knocking me out;

2. Things don’t always go as planned; and,

3. Tommy Knox was a great football player and a leader.

Tommy played a great game, proving that if he had been gifted great size, he would have played in the NFL and been a household name. He wasn’t.

After he graduated, I only saw him once when he returned to visit the school. From there, I never spoke with Tommy again. Once in a while I heard through the grapevine that he was doing well, working in New York. For me to pretend that he was a good friend would be a lie. He was just a guy that had a lasting impression on me.

Tommy died on September 11, 2001 in the terrorist attacks. He was 31 years old.

One thing I know, is if there had been any way to survive those attacks, Tommy would have done it – and he would have pulled out others with him.

Tommy’s family set up the Tommy P. Knox foundation here. In memory of Tommy, two underprivileged kids a year have a chance to attend our Alma Matter Seton Hall Prep – a school they would never have had the chance to attend without scholarships. Tommy is still changing the world, even though we all would prefer he be here.

For me, he will always be standing over me, arm outreached, lending me hand out of that mud — smiling and laughing.

– September 11, 2014